Decoding a Heavenly Script

June 2013

Decoding a Heavenly Script? You must be joking. For if the script indeed comes from heaven and is meant to be a divine mystery, how can we mere mortals ever hope to understand it?

But the Heavenly Script that we are talking about here is the work of man. It is made up of characters and symbols created many, many years ago. Their meaning was long lost with the passage of time, but the passion of an artist drove him to collect and record them, and ultimately created unique works of art out of them.

The characters are archaic Chinese pictograms. They and the symbols were found among Jiaguwen (甲骨文) - oracle bone script on tortoise shells and animal bones and Jinwen – (金文) bronze script on ceremonial bronze wares, on stone drums, stone tablets, earthenware rock carvings and rock paintings. They came from the years before Chinese characters were “standardised” into Zhuanshu (篆书) or seal script by Shi Huangdi, the first emperor of the unified China. To this day the seal script is widely used in seals, hence its English name.

Han-dling the Ancient script

The artist is none other than Han Mei Lin, who is well known for his fine achievements in the fields of sculpture, painting, calligraphy and porcelain, and who has several museums in China dedicated solely to his large body of work. Han was born in Jinan, Shandong Province in 1936. He recalls that he started to appreciate the beauty of seal script when he was only a primary school kid. He chanced upon an old book of this script and some seals in a temple in his neighbourhood. He was enthralled by the characters that looked more like pictures than writing, and, in his own words, he loved ‘playing’ with them instead of shooting marbles and kicking shuttlecocks like the other kids did. Later in his life, Han’s love for ancient Chinese scripts would further develop, and he would continue to regard them as painting rather than calligraphy.

It took the adult Han Mei Lin 34 years to collect tens of thousands of pictograms and symbols from even the remotest corners of China, and several years to record them. In 2008, his labour of love bore fruit - a book titled Tian Shu (天书) translated as “The Sealed Book” on its cover was published. It is amazing to go through this book to view Han’s handiwork of his precious collection.

Reaching for the Heavens

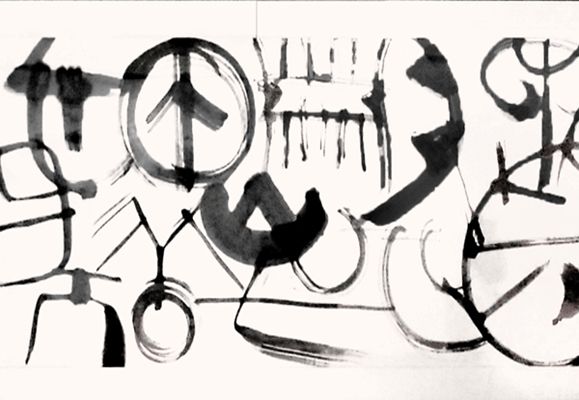

Tian Shu can also be translated as Heavenly Script, and this is the English name given to a piece of artwork that CapitaLand acquired from Han, proudly displayed in its Singapore board room. This work, in Chinese ink on rice paper and measuring 68 by 408 centimetres, is composed of characters and symbols from the sealed book. But what is special about it is that these are arranged and linked together, so that they form a bigger picture. All these were written, or shall we say, painted with the masterly brush strokes of Han, in the same tonal value of grey so that the viewer can focus on the shape of the characters. What fascinating characters these are – some resembling animals, others natural feature, yet others not seemingly resembling anything. One admires the composition as if it is an abstract painting - it does not have any meaning, but the thought that it does have some meaning but forever sealed by time makes it all the more intriguing. We see it as a mysterious script from heaven, which nobody can ever hope to decipher; we enjoy its beauty all the same.

To complete our story, we feature another piece of Han Mei Lin’s ink and brush work in the CapitaLand Art Collection, displayed at CapitaMall Asia’s headquarters. This is a painting of a bull predominantly in black but with traces of purple and brown, and it has a strong calligraphy feel. It is as if Han lifted one of the pictograms in the Sealed Book and expanded it to become a painting. Here, no decoding needs to be attempted for the character speaks all too plainly for itself.

This article is contributed by CapitaLand Chief of Art Management, Francis Wong Hooe Wai