Outback Stories

September 2013

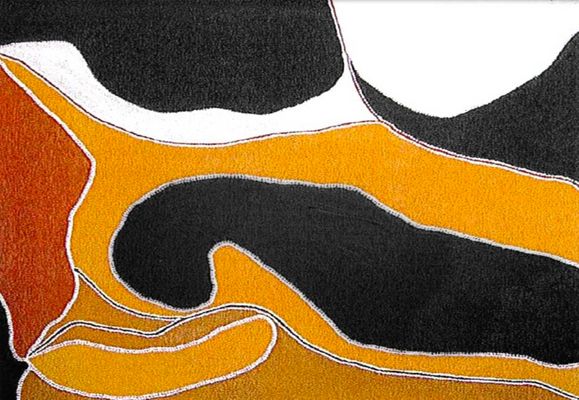

Prominently displayed in the lobby of Citadines on Bourke Melbourne, the Ascott Ltd’s stylish serviced residences in the heart of the city’s CBD, is a powerful painting about a story. As its title “Barramundi Story” suggests, it tells the tale of the Barramundi – a river fish of the sea bass family, native to Australia’s northern tropical waters, and is the work of the painter Freddie Timms, an Australian Aboriginal artist.

The painting immediately strikes you with its simplicity. Large and flat patches of white and charcoal and different tones of ochre make various irregular forms. In between these forms, little white dots string themselves into meandering lines. If there is a story about the Barramundi, it is certainly hidden; we can enjoy the work as an abstract painting – for the intensity of the colours, beauty of the shapes and texture of the “dotted lines” – all the same.

Birth of Modern Aboriginal Art

As recent as some thirty or forty years ago, one could never have imagined that Aboriginal art could adorn the interiors of modern buildings, not to mention gracing the exhibition halls of art museums and galleries, both in Australia and overseas. Regarded as the world’s longest continuing art tradition, it came in the forms of body painting, bark painting, rock painting, rock engraving, etc, dating back tens of thousands of years. And this has remained the art of this particular group of people who had no writing. Recording their myths and legends, this art was little appreciated outside their circle.

But in 1971 something happened. A school teacher and artist Geoffrey Bardon encouraged a group of Aboriginal men to paint a mural on a school wall in one of their settlements in Papunya, about 230km west of Alice Springs. It was a first display of Aboriginal art in a public space and it drew attention. Bardon also encouraged them to paint on boards and canvas with acrylic paints. Such artistic depiction of ancient stories often using sign and symbols gradually developed into the modern Aboriginal Art of today.

Birth of a Modern Aboriginal Artist

Freddie Timms’s artistic life can be seen in the context of the evolution of modern Aboriginal art. Born in 1946, Timms grew up to become a stockman following his father’s footsteps. A stockman is one who works in stations in the outback, responsible for taking care of livestock. Timms worked in stations throughout Australia’s East Kimberley region but in 1985, he became a gardener and subsequently an environmental health worker.

By the 1980s, the painting movement which started at Papunya had gathered strength, with talented Aboriginals becoming painters and Freddie was in the company of some of them. Eventually he, too, picked up the paint brush and started working on the canvas. His potential in art was soon recognised. Today, Timms is among the top 100 Aboriginal Artist in Australia.

Pigments from Mother Earth

In my private tour to Australia this July, I had the pleasure of first staying in Citadines on Bourke Melbourne, admiring Timms’s piece in the lobby, before flying off to Alice Springs the outback town in the heart of Australia. From there I saw two sites that furthered my understanding of Aboriginal art. One of them is the famed Uluru (Ayers Rock), where Dreamtime creatures left their mark in the land form, and ancient cave paintings can still be seen. The other is the awe-inspiring King’s Canyon, where ochre clay hardened to resemble rock – source of the earthy tone pigments of Aboriginal art, long before acrylic paints offer an alternative.

Back from the outback I stayed once again in Citadines and saw Freddie Timm’s piece there in new light. I still could not tell the story of the Barramundi fish, but could see in his painting the spectacular landscape of the outback, and the natural orche pigments from mother earth that he still insists upon using became ever so alluring.

This article is contributed by CapitaLand Chief of Art Management, Francis Wong Hooe Wai